Credit: Shutterstock

Enhancing Risk Management

NIST recognized the importance of managing risk for computing devices in the early 1970s and has been researching the topic ever since. NIST's work has been increasingly driven by a recognition that risk management should be a fundamental driver for every organization’s decisions about investments in cybersecurity and privacy—whether those investments take shape as people, processes, or technology. NIST considers managing risk to be an essential principle and process for organizations of any size or type to employ in planning and carrying out their cybersecurity and privacy programs and in making decisions about priorities.

Early Risk Management Initiatives

Initial Search for Risk Management Standards

In the early 1970s, the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) recognized the need to measure and analyze risk to information systems. Initial efforts included the Measurements Working Group of the NBS/ACM Workshop on Controlled Accessibility and several relevant publications. Around the same time, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued guidance requiring all federal agencies to report on the risk management processes they used to select safeguards for protecting the security and privacy of their information systems.

NBS held invitational workshops over the next few years to address the need for security risk analysis. In 1978, OMB Circular A-71 on Security of Federal Automated Information Systems required that agencies perform risk analysis, but there was not yet a standard method. In response, NBS came up with a method for performing risk assessments based on the work of Robert H. Courtney, Jr. of the IBM Corporation. Courtney's method, intended primarily for large data processing centers, described how an estimate of risk could be obtained by estimating the frequency of harmful outcomes and the financial impact that could result from each outcome. Recognizing the lack of empirical data for outcomes, Federal Information Processing Standards Publication (FIPS) 65 suggested an “order of magnitude approach” to approximating the real-world situation. This concept was not well understood, as illustrated by numerous attempts to be too precise in quantifying the input data to FIPS 65 and interpreting the results as having more precision than was justified by the input data.

In the following years, NBS searched for a candidate risk management standard. After evaluating existing approaches, NBS determined user satisfaction with all options was very low, and concluded it was too early to standardize on any of them. NBS instead focused on helping to address gaps in risk management guidance for federal agencies.

Emergence of Risk Management Tools

By the late 1980s, NBS and the National Computer Security Center (NCSC) of the National Security Agency (NSA) had assumed a joint leadership role to improve risk management. NBS had been closely monitoring the emergence of several new automated risk management tools. NBS observed that these tools reflected the latest desirable characteristics, including the use of computers as data gathering and analysis tools to reduce the time and resources needed, and the applicability of tools to both computer applications and data centers. NBS had arrangements with developers to exercise their automated risk management tools, and NBS and NSA established a Risk Management research laboratory at NBS to study approximately 20 products. The laboratory allowed NBS and NSA to obtain hands-on experience with risk management tools, develop criteria for comparing different approaches, and provide an environment in which federal agencies could do hands-on comparisons and evaluations.

Risk Management Model Builders Workshops

The early automated risk management tools did not adequately explain their methods. As a result, organizations lacked the technical information necessary to compare methods and apply the tools. Recognizing an opportunity to improve risk management models, processes, and, ultimately, tools, NIST and NSA initiated a series of Risk Management Model Builders Workshops from 1988 to 1994. Risk Management Tool developers and users—including NIST, NSA, other government agencies, and companies—convened to better understand the models they used and to develop a common and easily understood framework to provide a consistent understanding of the risk management process. The framework was intended to identify and define the components of risk management, describe their interrelationships, and include the concept of a safeguard selection capability.

While the workshops did lead to an initial framework, the community was not able to agree on the merits of using automated risk management tools for the following reasons:

- The empirical threat, vulnerability, and loss data needed for the risk management models was not fully developed.

- Some felt a formal risk management approach provided advantages since it enabled applying a consistent automated method across an organization. Others felt there were alternatives that were easier to understand and apply, such as installing baseline controls and performing tests and audits.

- Technology was changing much faster than the developers' abilities to keep their tools current and relevant.

A Risk-Based Approach to System Security

There was a major divide in the security community during the 1980s and early 1990s. Some preferred a rules-based approach to risk management, where systems were secured based on a static set of requirements. Others advocated for a risk-based approach where each system's risk was assessed and the security controls (i.e., security outcomes/countermeasures) selected based on that assessment. Every approach had major advantages and disadvantages, and each was better suited for different environments. Many commercial organizations preferred risk-based approaches because they had systems with a wide range of security needs and did not feel a one-size-fits-all approach was best. NIST had been supporting a primarily risk-based approach since the 1970s, such as defined by FIPS 65.

In the mid-1990s, NIST was tasked with writing a publication on best practices for security. NIST decided to base that publication on the content of NIST SP 800-12 and a security practices document from the British Standards Institute (British Standard 7799, A Code of Practice for Information Security Management (1993), which led to the development of ISO/IEC 27001). The new publication, NIST SP 800-14, Generally Accepted Principles and Practices for Securing Information Technology Systems, was published in 1996.

The next step for NIST was to help federal agencies measure security. NIST converted the security practices from SP 800-14 into requirements and determined how to measure their effectiveness based on five levels, providing a checklist in the form of a questionnaire so agencies could easily indicate the level(s) each security control was meeting (NIST SP 800-26, Security Self-Assessment Guide for Information Technology Systems). This was ideal for automation, and NIST worked with multiple companies to develop the Automated Security Self-Evaluation Tool (ASSET). The information behind ASSET was made available to everyone, and soon tools and services based on ASSET were available from federal agencies and private companies. NIST also held ASSET classes, distributed CDs, and developed a user's guide to help with ASSET adoption and use.

Around the same time, NIST developed a guide (NIST SP 800-30, Risk Management Guide for Information Technology Systems) that explained the basics of risk management, defined methodologies for performing risk assessments and other risk management-related activities, and gave recommendations for selecting security controls.

Expert Assistance for Agencies

Primarily during the 1990s, NIST Computer Security Division staff were encouraged to assist with the development and operation of other federal agency security programs. In at least one case, NIST was asked to review an agency’s IT program in its entirety from a security perspective and make recommendations for technical and managerial improvement.

NIST also established the Computer Security Expert Assist Team (CSEAT) to improve federal critical infrastructure protection planning and implementation efforts by assisting agencies in improving the security of their IT assets. The CSEAT provided an independent review of an agency's IT security program. The review was based on a combination of proven techniques and best practices, and it resulted in an action plan for agencies to cost-effectively enhance the protection of their systems, identify and fix existing vulnerabilities, and prepare for future security threats. A CSEAT review focused on areas derived from a combination of NIST guidance and OMB requirements.

FISMA and the Risk Management Framework

FISMA Implementation Project, Phase One

The E-Government Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-347) was signed into law at the end of 2002. Title III of the E-Government Act, known as the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002, tasked NIST with developing security standards and guidelines for the federal government for non-national security systems, including:

- Standards for categorizing information collected or maintained by or on behalf of each federal agency based on the objectives of providing appropriate levels of information security according to a range of risk levels;

- Guidelines recommending the types of information and information systems to be included in each category; and

- Minimum information security requirements for information and information systems in each such category.

NIST soon established a FISMA Implementation project. The first phase addressed the development of foundational security standards and guidelines, including FIPS 199, FIPS 200, SP 800-37, and SP 800-53.

Since 1983, FIPS 102 had been the primary certification and accreditation (C&A) guideline for federal agencies and had defined basic C&A concepts and terminology and outlined the processes for performing a C&A and managing a C&A program. Prompted by FISMA, NIST updated its system C&A guidance and published NIST SP 800-37, Guide for the Security Certification and Accreditation of Federal Information Systems in 2004, which provided C&A guidance that complemented other guidelines developed in response to FISMA. SP 800-37 was developed to help federal organizations manage risk and increase accountability by defining a process that leveraged results of risk assessments and security control assessments and provided the results to a senior management official to approve the security posture of a given system and have the official actually accept the risk of operating the system.

The most well-known guide published at the time was SP 800-53, which is consistently one of the most-downloaded NIST cybersecurity publications at about 400,000 downloads per year. Bringing together the concepts from FIPS 199 and FIPS 200, NIST created an extensive catalog of security controls that also defined a baseline set of controls for federal information systems based on their security categorization: low, moderate, or high. The adoption of the low, moderate, and high security categories was designed to make risk management easier by providing a starting point for identifying the controls needed for any particular system.

The original version of SP 800-53, published in 2005, included many of the same security controls as SP 800-26 and, in fact, superseded SP 800-26. With the publishing of SP 800-37 and SP 800-53, agencies were empowered to adopt sound risk management practices and build on existing programs and implementations. Over time, agencies gradually shifted to more rigorous and stringent practices, incorporating and implementing updates in accordance with updates to SP 800-37 and SP 800-53. By placing the risk management process and control recommendations in SPs rather than FIPS, NIST was better prepared to revise the guidelines in the future as security needs and technology changed.

SP 800-53 brought together the rules-based and risk-based approaches to risk management by specifying a common set of recommended security outcomes for each system, while allowing adjustments to take into account each system's unique characteristics and risk.

FISMA Implementation Project, Phase Two

The second phase of the FISMA Implementation project focused on assessing information security programs and security control implementations—determining if program requirements and security controls were in place, operating as intended, and producing the desired results.

The need to assess the information security program of an organization resulted in PRISMA—Program Review for Information Security Management Assistance. PRISMA provided a methodology to review and measure the maturity of an information security program based on nine primary review areas derived from FISMA, other NIST guidance, and recognized best practices. PRISMA also provided a corresponding tool.

Another important outcome of the second phase of the FISMA Implementation project was the publication of NIST SP 800-53A in 2008, designed to help agencies assess the effectiveness of security control implementations from the SP 800-53 catalog of security controls. SP 800-53A was developed as a companion document to SP 800-53 and provided guidance to develop security control assessment plans based on a common set of assessment procedures, and conduct security control assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of security control implementations.

Development of the Risk Management Framework

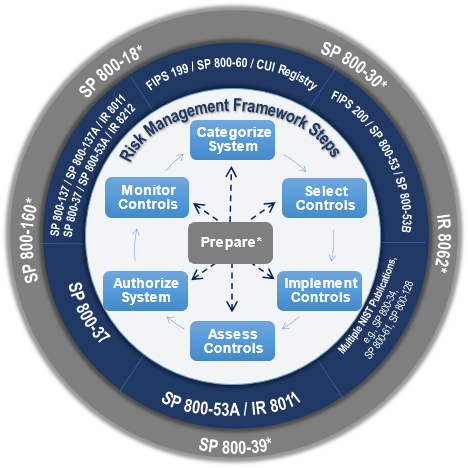

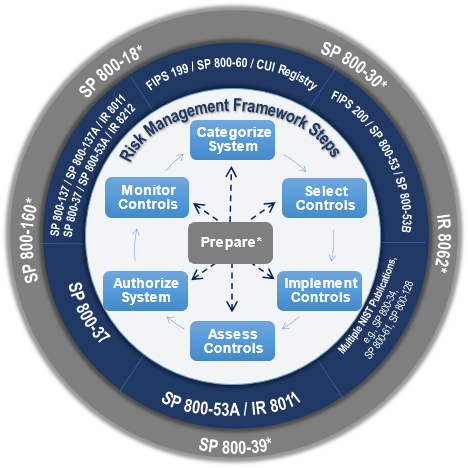

In the years following the release of the standards and guidelines noted above, NIST continued to refine its approach to risk management. In 2010, NIST expanded and re-focused the C&A perspective of SP 800-37 and developed the Risk Management Framework (RMF) as SP 800-37 Revision 1 along with related guidance:

The RMF provides a comprehensive and flexible risk management process that includes organization- and system-level planning, information and system categorization, control selection, control implementation, control assessment, system and common control authorization, and continuous monitoring.

The RMF is supported by a suite of SPs and NIST Interagency Reports (NISTIR) that provide additional technical and implementation guidance for each step in the holistic, repeatable process to manage risk. The RMF suite of guidance continues to evolve to address privacy and supply chain risk management, with updates to SP 800-37 Revision 2 (2018), SP 800-53 Revision 5 (2020), and SP 800-53A Revision 5 (2022). Additional guidance supporting the RMF implementation, such as guidance on automating security control assessments (ongoing) and conducting information security continuous monitoring program assessments, was released in 2020.

Notably in 2009, NIST initiated the Joint Task Force Transformation Initiative (JTF) an Interagency Working Group to produce a Unified Information Security Framework for the federal government. The JTF is chaired by NIST and is made up of representatives from the Civil, Defense, and Intelligence Communities. NIST and the JTF partners work together when revising the RMF and related publications to ensure that the revisions support civilian, defense, and intelligence agencies.

The NIST RMF and supporting publications have been adopted throughout the Federal Government, by state and local governments, private sector, and academia—nationally and internationally. Even organizations with risk management programs built on different risk frameworks often use SP 800-53 as a catalog of security and privacy controls since it is so comprehensive, widely reviewed, and freely available. The NIST RMF continues to provide innovative resources, such as publications in different data formats to increase useability, guidance on automating control assessments, and piloting a modernized approach for stakeholders to participate in NIST’s public comment process.

The NIST RMF also provided a basis for later critical work in the NIST's Cybersecurity Framework, Privacy Framework, and Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management efforts.

Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management (C-SCRM)

COMING SOON

The Cybersecurity Framework

COMING SOON

Privacy Engineering

NIST privacy work began nearly 50 years ago with the creation of computer security guidelines for implementing the Privacy Act of 1974 and its requirements for federal agencies and personally identifiable information (PII). Following these initial guidelines, NIST began developing standards for cryptography and encryption to address cybersecurity-related privacy events such as data breaches. In 2010, NIST released SP 800-122, Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), which recognized that privacy is broader than just protecting the confidentiality of PII.

2014 marked the first steps towards NIST’s treatment of privacy as an independent, albeit related, discipline to cybersecurity. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework V1.1 was released with a methodology for protecting privacy and civil liberties, recognizing that although cybersecurity can protect privacy, certain methods or measures can also create privacy risks. Volume 2 of NISTIR 7628 Rev. 1, Guidelines for Smart Grid Cybersecurity, focused on privacy and the smart grid, identifying privacy risks specific to the Smart Grid and distinct from cybersecurity risks.

NIST’s Privacy Engineering Program (PEP) was established with the mission to support the development of trustworthy information systems by creating frameworks, risk models, tools, and standards to protect privacy. PEP accelerated the conceptualization of privacy risk management by introducing a Privacy Risk Assessment Methodology (PRAM) and a set of privacy engineering objectives with the publication of NISTIR 8062, An Introduction to Privacy Engineering and Risk Management in Federal Systems. PEP also began integrating privacy guidance with cybersecurity guidance through numerous publications on broad topics, ranging from digital identity to Internet of Things.

PEP launched the Privacy Engineering Collaboration Space in 2019 providing an open, virtual platform for practitioners to share, discuss, and improve upon open-source tools, solutions, and processes that support privacy engineering and risk management. In 2020, NIST released the NIST Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy through Enterprise Risk Management. The Privacy Framework, modeled on NIST’s highly successful Cybersecurity Framework, is a voluntary tool used to help organizations identify and manage their privacy risks.

NIST continues to develop the fields of privacy engineering and privacy risk management by creating guidelines and resources to meet stakeholder needs. PEP has launched the Privacy Workforce Public Working Group (PWWG) to support the growth of a workforce capable of managing privacy risks. In addition, PEP completed a blog series focused on differential privacy to serve as the foundation for formal guidelines currently under development.

General Security Guidance for Executives and Management

Early Publications for Executives

In the 1970s, NBS and the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) published the Executive Guide to Computer Security. This was a pocket guide for executives in the Federal Government and the private sector that provided a broad background in managing computer security. Over 10,000 copies of this guide were printed and distributed by mail; to put that in perspective, the guide stated that there were only about 130,000 computers installed in the U.S. at the time. The Executive Guide to Computer Security was the first major product of the new Computer Security Program at NBS.

The contents of the guide were based on NBS Technical Note 827, Controlled Accessibility Workshop Report, which reported the findings of a 1972 workshop held jointly by NBS and the ACM. The workshop focused on five topics: access control, audit, electronic data processing (EDP) management controls, identification, and measurements. The goal of the workshop was for the attendees to "come up with fundamental principles of application and implementation, and where necessary, definitions within those topics."

In the late 1980s, NIST released a set of three publications on protecting information resources: Special Publication (SP) 500-169 for executives, SP 500-170 for management, and SP 500-171 for users. SP 500-169 replaced the Executive Guide to Computer Security with an updated, more detailed, and more formal publication for federal agency executives, and the other SPs provided similar information for management and users. All three publications addressed established computing platforms (e.g., mainframes) and newer technologies like personal computers.

The Information Security Handbooks

Since the mid-1990s, NIST has created and updated handbooks that provide an introduction to computer security. The first one, Special Publication (SP) 800-12, was released in 1995. It was far more detailed and comprehensive than the previous general security publications, covering many topics that were relatively new to NIST security publications. It also organized security controls into three groups: management, operational, and technical, which became a convention used by numerous NIST publications over the next two decades. Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of SP 800-12 was that, while it had some federal agency-specific content, it was also intended to be applicable to organizations other than federal agencies.

As technology and security both continued to evolve, NIST created SP 800-100, Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers. Finalized in 2006, it provided a broad overview of information security program elements to assist managers in understanding how to establish and implement an information security program. The handbook's topics were selected based on laws and regulations relevant to information security, including the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996, FISMA, and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-130. The handbook could be used by an organization's information security management team to help develop an information security program, or used as a helpful reference.

The latest iteration of the handbook is SP 800-12 Revision 1, An Introduction to Information Security, published in 2017. This is intended both for people who want an introduction to cybersecurity and for people who are not familiar with NIST security publications. It primarily targets federal agencies, but much of it can also be used by other types of organizations.

The NIST Interagency Report (IR) 7359, Information Security Guide for Government Executives, published in 2007, provided a broad overview of security program concepts to assist federal agency executives in understanding how to oversee and support the development and implementation of their agencies' programs. The same content in IR 7359 was also published in a supplemental booklet with a more reader-friendly format.

Planning

Physical Security Program Planning

One of the earliest security projects at NBS was the development of guidelines for physical protection of automatic data processing (ADP) systems (subsequently known as “mainframes”), the facilities housing those systems and their storage, and the storage media itself. When the guidelines were being developed in the early 1970s, physical security was generally considered sufficient to protect computers from threats because almost all computers could only be used by people who were physically at the computer. NBS staff worked with physical security experts from other organizations to draft guidelines. The final version was published in 1974 as Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) Publication 31, Guidelines for Automatic Data Processing Physical Security and Risk Management.

FIPS 31 recommended that organizations develop physical security programs, which included basic actions like conducting a risk analysis, implementing physical security protective measures, and conducting audits. What’s more noteworthy is that several of its key recommendations involved planning: determining local natural disaster probabilities, protecting supporting utilities, optimizing computer reliability, and planning for contingencies.

Contingency Planning

NIST began developing detailed guidance on contingency planning for automatic data processing (ADP) systems around 1980. Between 1981 and 1985, NIST published three important guides on contingency planning for mainframe computers.

Years later, when NIST staff prepared to start the work that eventually became SP 800-53, they realized there was a need for new guidance on writing contingency plans. NIST collaborated with external experts on contingency planning to develop SP 800-34, Contingency Planning Guide for Information Technology Systems, and the resulting publication was a clear success--at one point it was the most frequently downloaded NIST cybersecurity document--and was updated in 2010.

Having plans for information technology, like contingency plans and incident response plans, is important, but the plans can be far more valuable to an organization if they are verified from time to time. There are many methods for doing that, including tests, training, and exercise, and the methods leveraged to verify one type of plan can be applied to others as well. To help organizations take advantage of these methods and build programs around them, NIST developed SP 800-84, Guide to Test, Training, and Exercise Programs for IT Plans and Capabilities, finalized in 2006.

Incident Response Planning

Cybersecurity incident response planning became a significant concern in the late 1980s because of the Morris worm. Organizations with internet connectivity wanted a way to communicate with each other in case another worm spread, because at that time there wasn't a secondary communications mechanism in place for people to contact each other inside the United States or internationally. So staff from the new Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) Coordination Center at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), NIST, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Department of Energy (DOE) met and decided there should be a network for all to share information on incidents. The first international meeting was held at CMU to discuss how to handle incidents. This group ultimately became known as the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST), now an organization with participation from 98 countries. NIST funded FIRST for approximately 10 years.

Eventually part of FIRST morphed into what was known as the Federal Computer Incident Response Capability (FedCIRC). Proposed by NIST and launched in 1996, FedCIRC offered federal agencies incident response services provided by CERT and DOE, as well as system security reviews and other cybersecurity capabilities on a paid subscription basis. At that time, few federal agencies had their own incident response teams. FedCIRC was intended to be self-sustaining, but it did not have enough subscribers, so it needed to be moved to another agency that could add it to their annual budget. FedCIRC was first transferred to the General Services Administration (GSA). Shortly after the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created in 2002, FedCIRC was transferred to DHS and renamed the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT).

NIST recognized the need for agencies to build their own incident response capabilities, so it developed Special Publications on the topic. The first, published in 1991, was SP 800-3. In the next decade, a rise in incidents increased the urgency of incident response, so NIST replaced SP 800-3 with more comprehensive guidance. The goal of the new publication was to define basic terminology and concepts so agencies of any size and composition could put the necessary pieces in place, whether in-house or outsourced. This led to the release of SP 800-61, Computer Security Incident Handling Guide, in early 2004. SP 800-61 became widely adopted by all types of organizations, not just federal agencies, for establishing incident response capabilities, and is consistently one of NIST's most-downloaded cybersecurity publications. The most recent version was updated in 2012 to reflect the increasing need to coordinate among organizations.

In 2016 NIST published SP 800-150, Guide to Cyber Threat Information Sharing, which helped organizations prepare to exchange cyber threat information with one other. Exchanging cyber threat information allows organizations to leverage the collective knowledge, experience, and analysis capabilities of their peers, thereby increasing the overall awareness and security of an entire sharing community.

Security Plans

In response to the Computer Security Act of 1987, during the mid-1990s federal agencies created their own security plans and sent them to NIST for review. At that time there was no private sector capability for such large-scale reviews of system security plans. The guidelines federal agencies used for developing their security plans were not comprehensive, which led to a great deal of inconsistency in plans across agencies. This underscored the need for better security plan guidelines. The Federal Computer Security Program Managers' Forum drafted initial guidance, and NIST made numerous changes and additions to that material to create SP 800-18, Guide for Developing Security Plans for Information Technology Systems, which was finalized in 1998. SP 800-18 was revised and reissued in 2006 to incorporate NIST's FISMA publications.

Products/Testing

Products/Testing Laws/Regulations

Laws/Regulations Standards/Guidance

Standards/Guidance Events

Events